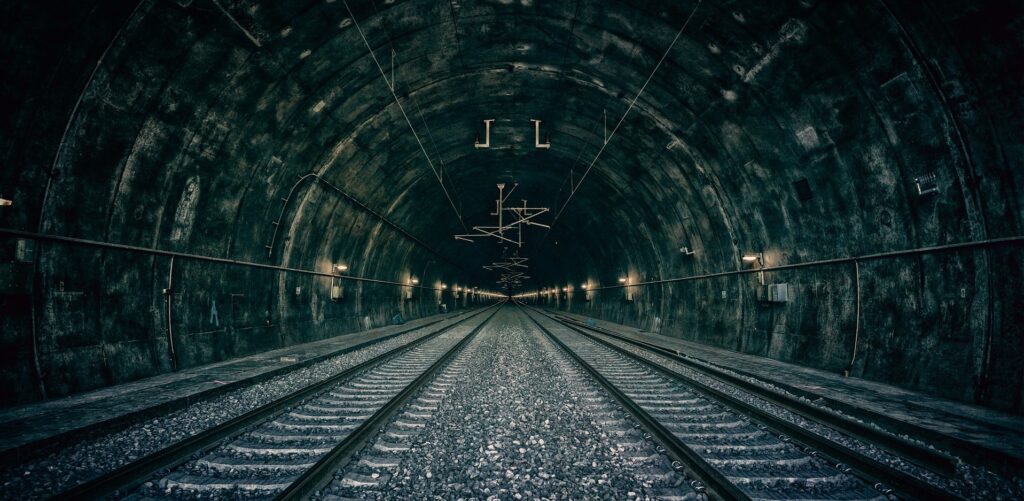

A fine mist had formed, so each blue flash seemed to electrify the air. Ali leant against a wall, hiding. He was wearing everything he owned, but the cold crept in like a rising tide. His feet were numb in oversized trainers. How could people live somewhere so cold? He peered into the darkness, pierced by the flashes and ghostly halos around streetlamps. At first glance he saw only a road through flat fields, and a railway curving down towards a tunnel. But there were also figures – blurred shapes in the mist. Some were alone, others in small groups. Dozens, scores, maybe hundreds.

Bridges ran over the railway, and on each squatted a police van with lights signalling their cold, repetitive warning: Stay away. The figures kept back for now, but it was early. They would drift closer as the night wore on, testing the police and the fences – or so Ali had been told. They knew the risks – pepper spray, batons, barbed wire, worse – but nothing would stop them trying. Their desperation scared Ali. He was only watching – it was his first night – but everyone here must have arrived sometime. And now they were shuffling through the dark, trying to reach the bridges. From there, the plan was simple: Drop on to a moving train.

When a train came, it was frighteningly fast – tons of metal screeching along frozen rails. Could anyone really dodge the power lines, land safely and make it through miles and miles of tunnel? Impossible, surely. But people said it had been done. Ali shuddered. That’s enough for tonight, he thought. He crossed the road and set off over the fields. Behind him, a train sped into the Channel Tunnel on its way to England.

***

‘More tea?’ Ibrahim asked, holding a blackened pot over Ali’s cup.

Ali shook his head. ‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘I’ve had enough.’

‘Got to keep your strength up,’ Ibrahim said, showing a mouthful of white teeth.

Ali smiled back. He wondered how Ibrahim kept this teeth like that. The ‘tea’ was so sugary that gritty grains came with each gulp. Did all Sudanese people make tea like this, or was it just Ibrahim?

‘You come from Egypt?’ Ibrahim said.

‘Yes,’ said Ali, feeling a slight twist in his stomach. This would be his first night in the tent city known as the Jungle, and his uncle had told him to stay with fellow Egyptians. ‘Thanks for letting me sleep here.’

‘No problem, my friend,’ said Ibrahim, smiling again. ‘We can’t leave a good boy like you out in the cold. You’re only – what – fifteen?’

‘Seventeen,’ Ali lied. He was fifteen, but he’d learned it was dangerous to be weak, old or young.

If Ibrahim thought Ali was lying, he didn’t show it. He picked up a chair leg and stoked the fire in the metal barrel which functioned as a stove. A square had been cut at the bottom for a grate, and a tin tube ran from the top to the roof of the tent.

‘Where are the others?’ Ali asked, draining his drink – a mush so sugary he almost had to chew.

‘Tunnel,’ Ibrahim said, frowning as he poured sugar into the pot. He added water and set it on the barrel. ‘Dangerous place.’

‘Why do people jump?’

‘Only way,’ said Ibrahim with a shrug. ‘Only way to England.’

Ali nodded, staring into the fire. ‘Why do they want to go there?’ It was Ali’s hope too, but he needed reassurance.

‘You’ve heard the stories,’ said Ibrahim. ‘You get a house in England. You get food, clothes, everything you want.’

‘Do you believe that?’

‘I heard the same about France – and look at us now.’ Ibrahim gestured around. ‘We are kings.’

‘Is that why you don’t go to the tunnel? You don’t believe England is better?’

Ibrahim waved a hand. ‘It might be. But Europe doesn’t want poor black people like me, or Arabs like you. We don’t look right, we don’t sound right, we don’t smell right.’ He sniffed his sleeve and laughed. ‘That part is true at least.’

Ali looked down at his hands.

‘I’m sorry,’ Ibrahim said. ‘You hope to go to England?’

‘Yes,’ Ali said, not looking up.

‘Don’t let me stop you.’ Ibrahim reached over and clapped him on the shoulder. ‘What do I know? Some say England is the promised land. Others say they have machine guns at the tunnel entrance to shoot us. The truth is in the middle, I hope.’

‘So do I.’ said Ali, fighting a sudden urge to cry.

‘It’s dull here,’ Ibrahim said. He had turned his back to throw wood into the fire. ‘You must have a story. Tell me your story.’

‘Nothing to tell.’ Ali didn’t want to think about his past – his story. ‘I lived near Cairo. I crossed the sea to Greece and came here. I walked, hitchhiked, took buses and trains when I could. Mostly I walked.’

‘I can see,’ said Ibrahim, glancing at Ali’s tattered trainers. ‘You came alone?’

‘I…’

‘I’m sorry. I shouldn’t ask. Tea?’

‘It’s OK,’ said Ali, holding out his cup. ‘My parents died. A bomb. I came with my uncle and we… we separated in Greece.’

‘I see,’ said Ibrahim.

At that moment, the four men who shared Ibrahim’s tent came in. Like Ibrahim, Ali guessed they were all in their 20s, strong but thin, clothes tattered like his own.

‘No luck, my friends?’ said Ibrahim. ‘Come and have some tea.’

Ali was given a sleeping bag and a place near the fire, but he knew he wouldn’t sleep. He hadn’t in weeks. Every few days he got so tired that he passed out in the daytime. But if he closed his eyes at night, he knew what he would see: a pair of shoes – tiny, soaking, white rubber soles turned up to the sky. They wrenched at his insides, but they were only part of the picture – the first frame of a film. If he let it continue, he would see legs, soft skin between socks and crumpled shorts. If Ali slept, he would see a mop of sodden black hair – his little cousin face-down on the beach.

So he didn’t sleep.

***

Morning was not exactly a relief, but the worst of night’s demons faded with the darkness. Ali waited for someone to wake. Ibrahim got up first, and Ali helped him light the fire. As the other men rose, Ali mumbled something about going outside, then spent the morning wandering the camp. He didn’t want to outstay his welcome.

The camp seemed chaotic, but Ali soon saw structure. Banks of compacted mud cut it into sections – rows or clusters of tents, usually home to people from one country or region. He sat on a bank for most of the day, watching people walking to and from the aid station. Pale sunlight kept the air warm enough, but as evening came he stood up, his legs numb, and returned to Ibrahim’s tent. The men – except Ibrahim – were preparing to leave.

‘Are they going to the tunnel?’ Ali asked Ibrahim quietly.

‘Yes. You will go with them?’

‘Yes.’ Ali was surprised the answer came so easily.

‘Then goodbye, my friend,’ said Ibrahim, squeezing Ali’s shoulder.

Ali walked with the men until they were near the tunnel, but slipped away when they greeted another group. He told himself it would be easier alone, that the police might not spot him, but he knew his real reason was the same one that had separated him from his uncle. They had parted in Greece, simply walking away from each other one morning. He needed to be alone with his pain – the agony his uncle must have felt ten times over for his son.

The night was even colder than the last, and Ali watched his breath turn to clouds against the star-strewn sky. Once again, police vans were on every bridge over the railway, so Ali walked downhill to the fence nearest the tunnel entrance. The grass here was littered with bottles, stones and other debris. Some way off, police were pushing back a crowd.

As Ali reached the fence, he saw a pair of wire cutters on the ground. A small hole had been made above, and in a heartbeat he was trying to force himself through. He ripped off layers of clothes. Jagged wire tore at his skin. For a horrible moment he was stuck. But he wriggled violently and fell through, like a fish dropped into a boat. He jumped up, reached what clothes he could through the hole, then ran to hide near the mouth of the tunnel.

He was panting, icy air scouring his throat. Somehow he was here, with nothing in his way. He steadied himself and heard a far-off sound. Peering into the tunnel, he saw a faint, growing light. Seconds later he fell on to stones as a train roared by. He got up at once, pressing himself against the wall but peering at the windows as they flashed past. He glimpsed people gazing out. Bored, he supposed. Keen to get to Paris. It was strange to be so close – feet apart, but in different worlds.

As the train’s red lights disappeared up the hill, Ali looked once more into the tunnel. There was space for a person even when a train passed – though being so close would be terrifying. He dug into himself for whatever courage was left. He couldn’t go back. There was nowhere, nothing and no one to return to. He didn’t know what he would find in Britain, but the journey ahead couldn’t be worse than the path behind. He stepped into the darkness.

This story came second in the National Association of Writers and Groups (NAWG) open short story competition 2018. It was published in the 2019 NAWG anthology, The Write Path – available here.